The spokesman of the Council of religions is optimistic. He believes our ability to live together as “one nation” goes beyond slogans. In 2016, he did his doctorate on the topic ‘Institutionalised religions facing poor people in a contemporary Mauritius’ and in the wake was decorated Officer of the Order of the Star and Key of the Indian Ocean. Even though he acknowledges the weaknesses of our multiculturalism, he is convinced by the potential of the “Mauritian fate.”

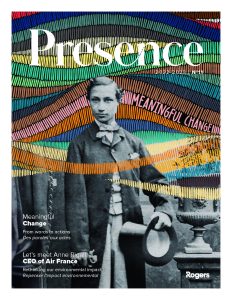

Photos. Gilliane Soupe.

The council of religions was created in 2001 after a recommendation of the UN to promote our multiculturalism. Throughout these 16 years, how has the dialogue among religions of our country evolved?

Actually, the council of religions goes back to 1994, when minister Sheila Bappoo decided to create a wise men’s committee to carry out a reflection on family. The committee was terminated the following year, but became a presidential committee. Indeed, in 2001 it rose from the ashes thanks to the UN. We have come a long way since. It was previously extremely taboo to address the topic of religious mix, even though it was topical. Edwin de Robillard was a great visionary and was the pioneer of all the initiatives in favour of national unity and inter-religious dialogue before our independence.

I believe that today, in the era of globalisation, we discuss more about what was taboo, especially when we know that the people are more informed and educated. With the advent of commercial radios, people began to speak their mind. We dare to tackle this matter in politics and even to denounce what was taboo before. We are in Mauritius, in a melting time where there is an evolution. It is closely related with what it is happening in the world. The intercultural question is becoming an international concern. There are great challenges of integration, whether it is for migrants, expatriates or religious fundamentalists. André Malraux said: “The 21st Century will be religious or it won’t be.” Hand in hand, we are aware of our interculturality, there is a re-emergence of the spiritual awakening. The bottom line is that we are in an extremely interesting period for the world and for Mauritius.

Why is it so important to talk about religious mix?

I am convinced that if we have to find the Mauritian fate, we must go through this exercise of truth. We must admit and thank Navin Ramgoolam and his government for the creation of the Justice and Truth Commission. Of course, it is necessary to know what to do with it. But at least, the institution and the authoritative mastodon of data shake us up, together with our habits and our structures. We won’t be able to set a Mauritian modus vivendi – which is already set up, but which still needs to evolve – if taboos persist. Otherwise, we continue to convey a bunch of unintentional stereotypes. This is the starting point of my thesis: human, political, economic challenges, which all concern us, end up being mixed with the panel of diversities all around Mauritius.

André Malraux said: “the 21st century will be the spiritual era or simply won’t be.”

You talk about “the Mauritian fate” whereas we often hear the word “mauricianisme.” What is the difference?

I haven’t used this term which is overused. The “ism” are interesting, but are to be used with caution because they are suggestive of an ideology. And the ideology is often political. The term “mauricianism” is now employed for no apparent reason, but it can be unloaded all that has tarnished it before. I am convinced that there is a process which started long ago and which made a historical milestone from our independence in 1968, because it was necessary to take the lead and to handle our own destiny. This process isn’t disconnected from the rest of the world despite our insularity. Things are moving forward. But if we don’t do anything, we’ll be repeating the same pattern we’ve seen before. During my research, people told me it’s not only because of their faith that they are hospitable. There is also something else. And that is what, we, researchers and anthropologists, try to theorise.

Is there a beginning of an answer?

In what they do, people try to be consistent with their sacred texts. But they don’t necessarily do it in the name of their religion, but in the name of something else. The history of mankind is filled with attempts to try to understand this “something” from the innermost depth of our souls. All kinds of societies tried to figure it out. Before the Westerners brought the bill of Human Rights, the Africans had something which they called “Ubuntu.” Which means: “I exist because you are.” The bill of Human Rights is yet another example of that “something” and we do not measure its philosophical reach. This is the case in Mauritius. We naturally created a term, which says something about this desire: lakorite (to live in harmony). This word was invented on Mauritian soil. We can’t find the correct translation for this term. It is much deeper than “agreement” in French or “harmony” in English. It is a whole way of living according to the Mauritian style, forged from the colonial era until today and which continues to have a deeper meaning. We find this notion in all communities. We can think of a human being venerating his sacred text, and sometimes going beyond what is being said in it. It is an ideal to achieve, and a reality at the same time.

From this point of view, could we say that Mauritius is a model for the rest of the world?

Yes, even if it is not a perfect model. I am convinced that each one of us has a role to play. We all have responsibility. We need to wonder what we are doing for the betterment of things. When I read the Atharvaveda, I saw something that could be learned from our Hindu brothers: hospitality as a sacred act. It is what Mauritius can teach to the world – this warm-hearted side which makes us more welcoming than any other place. We can choose to live our lives by aiming to improve our own well-being. Many of us live that way, not viciously, but passively. We are formatted by this way of living. But there is another road where we are active and developers of humanity. This is where I put the onus back on us. We have to question ourselves, to know to what extent we want to be active citizens, to have a say in the debates. It is our biggest personal omission. That does not mean that we have to become the world’s saviour. But we have to address the issue.

How is the council of religions helping in this process?

We are focusing on an old programme: the university training of Mauritian citizens eager to know the other who will then engage themselves, be it in politics, diplomacy or human resources management, but with an intercultural encounter. We are currently fine-tuning a course which already exists at the University of Mauritius: the ‘Peace and Interfaith Certificate’, so that it becomes a certificate or a degree with employment opportunities. It is a big project. Then, there are interventions, for which our help is needed. We are not above all religious leaders. We work towards social cohesion. We are also tackling the drug problem along with the Collectif Urgence Toxida.

We talked about politicians and citizens. But does a private company have its role to play in finding the Mauritian fate?

Of course, we are talking about the Mauritian nation’s future. There are two things. Firstly, inside the group, how can we pursue this reflection carried out on alter capitalism? It is undeniable that we are in a globalised system embodying capitalism, neoliberalism, and a financialised system. We cannot condemn this system, but we should be conscious of it. Inside this system, we can take positive action which always focuses on the human. Social entrepreneurship, for example, is the act of creating a company with lucrative purpose, but which takes more time to earn profit because the employees are from an impoverished background. We just have to get started and lay the foundations. Muhammad Yunus, for example, created the micro-credit scheme to be able to lend money to the poor and 25 million people were able to move out of poverty. Once again, it’s up to us to allow an equitable system. It is necessary to question ourselves on how we are helping our employees to thrive. How do I make sure that my employee is not only a workforce, but a human being contributing to the work and bringing me the necessary force I need? There is also the external input. Once again, it is a question of individual ethics. A company can continue to invest in CSR policy. But can we think of funds which go beyond the mandatory funds which would be independent funds developed by the company, and would contribute to this Mauritian enterprise? With details which would take into account the group’s priorities and the needs to achieve the Mauritian fate.