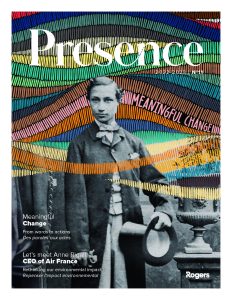

The pioneer and the successor

Around 75 years ago, Georges L’Aiguille was supplying clean energy to the Bel Ombre sugar mill. He gathered all his memories to share them with Christian Nanon, Rogers’ sustainability champion in Bel Ombre. Here are selected excerpts from a meeting full of anecdotes and emotions.

Despite an age gap of several decades between them, they share a common story since they both, separately, paved the way for sustainable initiatives in Bel Ombre. For Christian Nanon, Rogers’ Sustainability Manager, this is currently reflected in the implementation of several concrete actions, ranging from the creation of carbon sinks to the regeneration of the lagoon, to beekeeping or composting projects. For Georges L’Aiguille, an old man with a gentle smile, we need to go back to the 1950s.

This gentleman, who is the son of a wood dealer and the youngest of 13 children, is a true memory book. His age – 99 years old – and his life story commands respect. ‘‘I never met my father and barely went to school. I had no choice then: I had to work. It was in sugarcane fields with my mother, at first, and as a shoemaker afterwards. My bicycle was all I had. I cycled from one odd job to another,’’ the elderly gentleman recounts with a soft voice. To satisfy his wanderlust, he enrolled in the army as a sacristan, whereby he visited Egypt and Syria. He finally settled down in 1954, at the age of 30. He then became responsible for producing power for the Compagnie Sucrière de Bel Ombre (now Agrïa). But not any kind of energy: one which is carbon-free, at a time when climate change was not yet a cause for concern…

Like Monsieur Jourdain

That morning, Georges welcomes us to his place in Bel Ombre. His gestures are slow and gentle. We can feel that time elapses in a different way here, at Hibiscus Lane, which is a few yards from the sea. In the garden, a bed of plants basks in the sun. The kettle, whistling in the kitchen, announces the first round of coffee. ‘‘I’m very glad to meet you, Georges. By producing hydroelectricity, a renewable and carbon-free energy, you showed us the way, and we want to go further along that road,’’ Christian says, kickstarting the discussion.

Who would remember that Bel Ombre was already caring about the environment three-quarters of a century ago, just like Monsieur Jourdain, who unknowingly spoke prose? A group of elders, at most, one of them being Georges. This is because the hydroelectricity was produced at the small power station, on the river bank, at Frederica. ‘‘I started as a mechanic apprentice,’’ he proudly recounts. ‘‘I learned and climbed the ladder to become the mechanic responsible for the generating unit (the very heart of the station).’’

According to his son Jean-Philippe, whose childhood memories taste like guavas, pom zako (custard apple) and swimming, Georges was the ‘‘eyes and ears’’ of this machinery. “On weekends, our father used to take my brothers and sisters camping near the power station. He would spend the day greasing the valves and inspecting the turbines while we were playing in the river, picking fruits… It was like a holiday for us. He even set up a vegetable garden there.”

Back to hydropower?

He laughs, almost surprised, when we ask him to give some details about his job: “Ayo, mekanik la ti bien simp! Pou gayn kouran, ou bizin de kikzoz: denivle ek fors dilo,” he exclaims (Editor’s note: It was basic mechanics! We needed two things to produce electricity: a variation in level and the force of moving water.) “This electricity was not only powering the sugar mill, but also the households across the estate,” he adds, with a sense of achievement.

In his work, Christian draws inspiration from the past to look forward to creating a more sustainable and eco-friendly environment. Should we revive hydropower? It is in the pipeline. “Potential sites have been earmarked, and studies are currently being carried out,” he indicates. Georges’ eyes light up again. “Eski ou pou kapav ?” he asks. (Editor’s note: Will you be able to do it?). “It will depend on the production capacity, which itself depends on water flow and kinetic energy,” Christian answers. Georges nods: ‘‘You know more about this now than I do.’’

The whistling from the kettle does not weaken. Georges – whose nickname is “the president” – stops talking. He seems to be lost in his thoughts. When we look at his face, we guess that he left a part of himself in Frederica, on the other side of his life, where he harnessed the power of water to produce electricity for three decades.