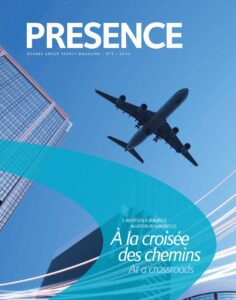

After just over four hundred years of human settlement, Mauritius is today confronted with growing environmental issues that have contributed to the gradual degradation of its coastal and marine biodiversity.

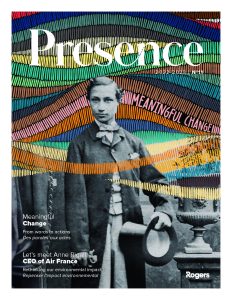

photos : reef conservation | deeneshen sabapathee | coi françois rogers | mmcs | rachel de spéville

Globally, pollution and the impact of development represent a permanent threat for coastal and marine ecosystems which, from a biological point of view, are some of the most productive in the world. We also now recognise that climate change poses an urgent global environmental problem.

A report on the future of the environment in Africa published by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) indicates that the use of fossil fuels and the manufacturing of cement have led to the release of some 270 billion tons of carbon globally since the start of the Industrial Revolution. Global warming is likely to lead to a rise in sea levels accompanied by the displacement of low-lying populations, with the disappearance of some island states and changes to and reductions in agricultural production.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change average global temperatures rose 0.6°C during the last century. Marine environments could be seriously affected as an increase in sea temperature of 1°C to 2°C could result in major coral bleaching in the west of the Indian Ocean, affecting the economies of sea-bordering countries and islands.

The rise in sea level caused by climate change in the world’s 52 small island states – four times above the global average according to some estimates – continues to constitute the most urgent threat to their environments and socio-economic development. The annual economic cost of their growing vulnerability could run into trillions of dollars.

Mauritius has 322 kilometres of coastline, 150 kilometres of coral reef and 243 square kilometres of lagoon area, an exclusive economic zone of 1.9 million square kilometres and rich marine biodiversity with more than 1,650 known species. Like most oceanic islands, its ecosystems and biodiversity have been affected by such factors as demographic pressure, the accidental or selective introduction of non-native species, the conversion of land for agriculture, hunting, urban growth and pollution. As result of these pressures, a considerable number of plant and animal species are threatened with extinction or have already disappeared, the most infamous case being that of the dodo. Eventually hunted out of existence, it was also the victim of the introduction of alien species. Additionally, the overexploitation of land and sea turtles has contributed to their decline. The burning of sugarcane in Mauritius is also a frequent cause of the destruction of insect, bird and reptile habitats, as well as being a source of air pollution. The change brought to freshwater habitats by pollution is, like overexploitation and selective exploitation, another cause of dwindling biodiversity. Coral reefs are zones with high biological potential for plant and animal life. They are both a habitat and a major food source for many sea species living in Mauritian waters but also vulnerable organisms whose progressive decline should serve as a wake-up call.

Globally, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 20% of coral reefs have disappeared, 20% are severely degraded and 50% in an unhealthy state. In all areas of small island developing states (SIDS), coral reefs, which are their first line of defence, are already heavily affected by the rise in seawater temperatures. The reduction in coral reef cover – some 84 million acres over the last two decades – will cost the global economy some US$11.9 billion, affecting particularly the SIDS, according to the SIDS Foresight Report published by the UNEP in early June 2014.

In Mauritius, the degradation is linked to a range of factors, including some natural ones such as coral bleaching, the proliferation of algae, climate change, soil erosion (some 18,500 square metres of beach have been lost in the past decade), sedimentation, tropical storms and the presence of a predator, the crown-of-thorns starfish.

The degradation is accentuated by direct human factors including the damage caused by boat anchors and fishing nets, as well as the illegal trade in live coral removed from the lagoon, pollution caused by various forms of waste, and the infiltration of chemical fertilisers, insecticides and pesticides, which increase nitrate levels in seawater resulting in a proliferation of green algae.

Like his fellow-countryman, Francois Sarano (see page 12), Dr Edouard Obadia, who is specialised in hyperbaric medicine and reanimation, worked with Captain Cousteau and his team for two months in 1979. He has also dived throughout the world since he was 17 and has a level of expertise equivalent to that of a diving instructor. “For the last twenty years, the damage caused by humans to marine flora and fauna has become clearly visible, notably as a result of net fishing that damages the whole ecosystem. Corals take decades to reconstitute whereas some factory ships destroy everything in a couple of days. And that is dramatic.”

Dr Obadia has been diving in Mauritian waters since the mid-Eighties. He says he has seen the presence of a lot of dead coral of late but also others in the process of regrowth. “People perhaps are being a little bit more careful these days. I think that awareness is growing that the sea and the land are resources in which we have a common interest.”

As well as the destruction caused by fishing, marine and coastal habitats and species are also threatened by mass tourism, which damages coral reefs as a result of the pollution from boats, hotels and other buildings, and activities such as excessive walking on the coral reefs or their removal as souvenirs.

Moreover, the felling of mangrove trees removes a source of protection from sea swells and accelerates coastal erosion as well as salt-water penetration. As mangrove cover declines, the breeding grounds for shrimps, crabs and other species disappear.

“The Mauritian coastline used to be almost completely surrounded by mangroves that acted as a barrier. When people started to live on the coast, they were removed to provide sea access. In some areas, the mangroves were replaced by casuarina (filao) plantations,” explains Jean-Claude Sevathian, the Rare Plant Conservation Officer of the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, an NGO working for the rehabilitation and protection of endemic species in Mauritius.

When people first settled in Mauritius in the 16th century, the island was full of plant and animal life. After more than four centuries of human habitation, only some 2% of primary forest remains. Numerous endemic animal and plant species have disappeared and the marine ecosystem has gradually become impoverished. The island is today ranked third globally for the percentage of endemic plant species threatened with extinction. It is also among the 25 hotspots designated for priority conservation globally because of its unique biodiversity. It’s an alarming picture which clearly shows the urgent need to act before we reach the breaking point which so worried Captain Cousteau…