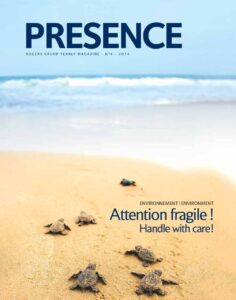

Drawing on his extensive expertise and keen interest in the field of marine conservation, Tom Hooper provides some thoughts on the current state of our marine environment and the need to strike a balance in how we use the sea.

photos : eugène vitry | deeneshen sabapathee | reef conservation françois rogers | alain gordon-gentil

What was the objective behind the setting up of Shoals Rodrigues?

We wanted a longer-term legacy for the work that had been started by the Shoals of Capricorn Programme, a project initiated by the Royal Geographical Society in London. We had established a small, low-cost marine research centre that had strong local ownership and community links and saw the need and potential for this to continue.

Scientists need to gather data over many years, for example to show long-term trends in populations, but rarely do they have the ability to stay in the field for long periods of time. We showed that you could link the scientists together with well-trained local research assistants who could take samples and measurements. In this way, Shoals Rodrigues has supported hundreds of scientists and helped to collect data for internationally important scientific studies.

The other crucial benefit of this approach is that the knowledge and skills stay on the island. Compared to some projects, we were able show that you can

run a small and cost-effective research centre which can provide vital support to the local Government

and community.

What do you regard as your greatest achievement during the five years you spent on the island?

From the moment that we arrived in 1998, the Rodriguan people and authorities were genuinely interested and supportive of the work that we wanted to do. Most of all, I am really proud of the long-term legacy that was established and the strength that continues to this day. In the first couple of years of setting up Shoals Rodrigues, there were a number of school children who started attending ‘Club Mer’, our Saturday morning club, where we taught them about the sea and how to swim, snorkel and dive. Several of these children have now grown up and ultimately became employees of Shoals Rodrigues, and in turn started to teach other Rodriguan children about their magnificent marine environment.

How important is community involvement in the success of any environmental endeavour?

It is important to remember two things about the sea. First of all, it can sometimes be a bit like the Wild West; it is a big, inhospitable place where it is difficult to manage and enforce laws. Secondly, that no-one likes being ‘done to’; we all like to feel that we have a stake in our destiny. What I have learned through my time in Rodrigues and back in the UK is that people who use the sea for their leisure or livelihood have to be involved in decisions if they are to be accepted and complied with. Decisions are often difficult and emotional, but the majority of people are prepared to keep a positive and forward-looking focus.

Having spent most of your career as a marine biologist in the Indian Ocean, what are your observations on the current state of our coastal and marine environment?

I have been lucky enough to dive and snorkel around the near-pristine reefs of St. Brandon, north-north-east of Mauritius. When you have seen huge groupers swimming amongst countless reef fish and gangs of sharks herding small fish in the shallow lagoons, it makes you realise

how impoverished the reefs are in other parts of the Indian Ocean. On the other hand, I have also seen reefs that have been dynamited in Tanzania and watched young men spear-fishing for huge rays and groupers, displaying them proudly, as they inevitably undermine their own future as fishermen.

On a global scale, I am genuinely worried for the future of our seas. The combined impact of climate change, acidification, overfishing, agricultural run-off and plastic pollution is already putting incredible pressure on our oceans. However, on a small scale I have seen some really encouraging projects in which fishermen and local people have taken their future into their own hands and set up and enforced marine reserves.

As human society has developed, we have also grown the ability to have a greater and greater impact on the marine environment. At the same time, our knowledge of the sea has also become much more sophisticated which allows us to see and understand these impacts. My hope is that we will use this knowledge wisely and with consideration for what we are leaving behind for our children.

What is the correlation between the coastal and marine environments and how does the degradation of one impact on the other?

The two are intrinsically linked. In Mauritius, there is a direct link between the plastic pollution from the island itself but also from plastics coming from South-East Asian countries on the ocean currents. There’re also the problems of agricultural chemicals and human sewage. So if you don’t manage your coastal environment – and for all intents and purposes, the whole of the island of Mauritius is coastal –you’re going to have issues with your marine environment, which in turn impacts on tourism and fisheries.

The shallow lagoon and coral reefs are also very important for the protection of coastal villages and town. They are an essential part of the island’s natural defences against sea-level rise, storm waves and cyclones. If you had to replace them commercially, that would run into hundreds of millions of dollars.

What about phenomena such as tsunamis, El Niño and so on? Does this degradation have an impact on their intensity?

Whether in Europe or the Indian Ocean, without doubt the greatest threats to the marine environment are from climate change. The resulting changes in water temperature, sea-level rise and acidification of water are a triple whammy for coral reefs and other marine life. Coastal communities in the Indian Ocean are in the front line of these changes and are all too aware of how devastating the loss of coral reefs will be for livelihoods. The challenge for us is how we equitably reduce our emissions across the globe and it is frustrating to see such poor progress in climate negotiations. At a local level we can do as much as we can to reduce our own dependence on fossil fuels and embrace low-carbon technology.

At the same time, across the globe we also need to think about how we reduce the stresses and pressures on our environment and this is where we have a responsibility for our own environmental stewardship. For example, we need to think about how we can use agricultural chemicals more wisely, how we can reduce and treat our wastes and how we can manage our fisheries so that they are able to produce fish for decades to come.

What steps would you recommend in terms of marine conservation?

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are one of the best tools in the box. By reducing some of the more damaging human pressures you are able to create oases of life that can support and replenish the wider marine environment. They are a tool that sounds good in theory, but the challenge is in selecting a network of sites that provide genuine protection for all of our different habitats and species. They are controversial because they will have to limit human activities but if they are well managed and enforced they have shown to be really effective at safeguarding marine life.

Secondly, I think it is important that we all recognise that we have a stake in our marine environment. The UK is an island, and has a strong history of seafaring and exploration but I think that we are too disconnected from our marine heritage and forget how important a part it plays in our lives. I know that people in Mauritius and Rodrigues are proud and protective of their sea and lagoon and I think the more that can be done to show and teach people about the lagoon and its magnificent beauty and fragility the better it will be for its future.

How important is the contribution of business companies in trying to redress the situation?

At no cost to us, the sea breeds and grows fish that can be caught, processed and exported. It provides a playground for us to go diving, snorkelling or sailing and coral reefs that provide natural defences that protect our land from waves and storms. We call these ‘ecosystem services’. Attempts have been made to quantify the enormous value of our oceans, which extend to areas such as regulating climate and recycling our wastes. All these things are for free and I fear that we take them too much for granted. There is a strong commercial desire to use natural resources at an unsustainable rate and we are learning that this can have repercussions. Across the globe, there is a gradual move for the corporate sector to take a longer-term and holistic viewpoint in their planning. Fish are the ultimate renewable resource. If we look after populations then they will keep producing more and more. Corporations play an important role in helping to ensure that the provisions and benefits that they get from the sea are well maintained and keptintact so that fishing and so on remains a sustainable activity. Mauritius is the same as the UK in the balance that needs to be achieved between the different ways we use the sea. There is inevitably tension between different interests and the impacts that they have on each other. I think Government has to play an important role in achieving the right regulatory environment to manage these.

A passion for the sea

Tom Hooper, aged 45, has always wanted to be in, on or under the sea. He studied marine biology and tropical marine ecology at university and has spent most of his career working on marine research and conservation projects in the Indian Ocean. He first came to Rodrigues in 1999 with Tara, who later became his wife, to work for a project called the Shoals of Capricorn that was led by the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society in the UK. Two years later they set up Shoals Rodrigues. Tom left Rodrigues in 2004 and in the same year was awarded an MBE for services to marine conservation. Back in the UK, he spent the following six years as the manager of a project called Finding Sanctuary to plan a network of Marine Protected Areas around South-West England, a 93,000 square kilometre area of sea! Tom now works for Europe’s largest conservation organisation, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, as head of Marine Policy.